Amidst rifle shots and whooping cries in the pre-dawn

darkness, a veteran Irish-American cavalry soldier and a little girl seek shelter

from attacking Apaches in the ruins of a Catholic mission; as they hurry

through the dilapidated chapel, both pause, turn, and genuflect in the

direction of the sanctuary before racing on to their escape.

This scene, from director John Ford’s Rio Grande,

perfectly embodies the way a Catholic upbringing manifests itself in the work

of Catholic artists; whether or not they drifted from the faith later in life, their roots remained. Not

only Catholic imagery, but also notions of grace and redemption, sin and

innocence, and the importance of adhering to principles even when the world is

against you—all these elements of a Catholic mentality are often so deeply embedded

in the perspective of Catholic filmmakers that it cannot help but shine through

in their repertoire. Three of Hollywood’s

most brilliant directors—Frank Capra, John Ford, and Alfred Hitchcock—were all

raised Catholic, though they did not all exactly fit in the “practicing,

faithful Catholic” category. However, regardless of any apparent imperfection

of their personal faith lives, Catholic sensibilities were deeply entrenched in

their way of thinking and consequently in their films. Even if their faith was

somewhat battered and damaged, like the chapel in the scene from Rio Grande, and even if they moved in a

world rather hostile to Catholic principles, they almost unconsciously turned

to give it reverence, by the content, color, and characters that make up the

focus of their work.

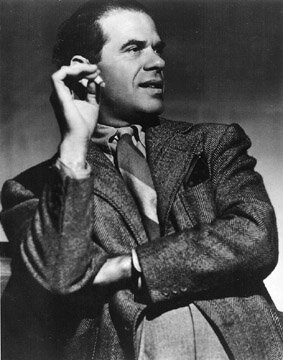

An Italian Catholic, Frank Capra was a champion of hanging

on to beliefs and ideals when it seems least likely they will triumph. He had

an abiding Catholic confidence in man’s basic goodness, and a likewise Catholic

respect for the common man. His films celebrated the ordinary man standing up

against corruption, greed, and selfishness; he focused on the need for

self-sacrifice to bring about change in a wicked world. Mr. Smith Goes To Washington is Capra’s moving call for selfless

patriotism, in the story of a young, idealistic politician who is “crucified,”

as one character puts it, when he takes a stand against corrupt government; it

is only when the hero sticks to his ideals, even when they are a “lost cause,”

that he undergoes a political death and resurrection and comes out victorious.

The same basic concept is found in Mr.

Deeds Goes To Town. Arguably Capra’s most famous, It’s A Wonderful Life is a masterpiece of Catholic sentiment,

examining the heroic choice to live a quiet life of selfless duty even if it is

unglamorous or materially unsuccessful. You

Can’t Take It With You runs along similar lines, when Capra contrasts the

bitterness and heartbreak that results from pursuing only material pleasures

with the contentment and peace possessed by those who set their sights higher

and trust God to provide for them, like “the lilies of the field.”

An Italian Catholic, Frank Capra was a champion of hanging

on to beliefs and ideals when it seems least likely they will triumph. He had

an abiding Catholic confidence in man’s basic goodness, and a likewise Catholic

respect for the common man. His films celebrated the ordinary man standing up

against corruption, greed, and selfishness; he focused on the need for

self-sacrifice to bring about change in a wicked world. Mr. Smith Goes To Washington is Capra’s moving call for selfless

patriotism, in the story of a young, idealistic politician who is “crucified,”

as one character puts it, when he takes a stand against corrupt government; it

is only when the hero sticks to his ideals, even when they are a “lost cause,”

that he undergoes a political death and resurrection and comes out victorious.

The same basic concept is found in Mr.

Deeds Goes To Town. Arguably Capra’s most famous, It’s A Wonderful Life is a masterpiece of Catholic sentiment,

examining the heroic choice to live a quiet life of selfless duty even if it is

unglamorous or materially unsuccessful. You

Can’t Take It With You runs along similar lines, when Capra contrasts the

bitterness and heartbreak that results from pursuing only material pleasures

with the contentment and peace possessed by those who set their sights higher

and trust God to provide for them, like “the lilies of the field.”

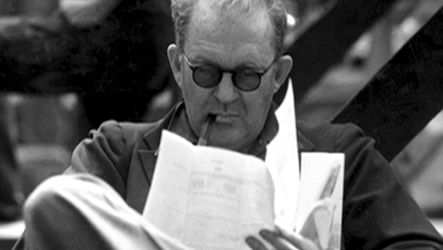

It doesn’t take much analysis of John Ford’s films to

realize that his Irish-Catholic heritage was the wellspring of inspiration for

the vast majority of his work. Ford loved to draw on the characters and imagery

from Irish-American history; Irish and Catholic characters abound in his films.

His pet project was The Quiet Man,

set in a small, Catholic, tradition-steeped Irish town; essential to the plot is

the fact that the characters look to their local priest for advice and help.

But Ford’s work also overflows with subtly Catholic themes of grace and

salvation. Stagecoach, for instance—often

hailed as the definitive Western—takes a motley handful of imperfect

characters—a drunk, an outlaw, a prostitute, a gambler, and a social snob—and

charts their journey through a purgatorial experience of mutual suffering. One

lesser-known but excellent Catholic-themed work from Ford is 3 Godfathers, in which three bandits

become the unlikely godparents and self-sacrificial saviors of an infant in the

desert, in a way that parallels the story of the three Magi.

It doesn’t take much analysis of John Ford’s films to

realize that his Irish-Catholic heritage was the wellspring of inspiration for

the vast majority of his work. Ford loved to draw on the characters and imagery

from Irish-American history; Irish and Catholic characters abound in his films.

His pet project was The Quiet Man,

set in a small, Catholic, tradition-steeped Irish town; essential to the plot is

the fact that the characters look to their local priest for advice and help.

But Ford’s work also overflows with subtly Catholic themes of grace and

salvation. Stagecoach, for instance—often

hailed as the definitive Western—takes a motley handful of imperfect

characters—a drunk, an outlaw, a prostitute, a gambler, and a social snob—and

charts their journey through a purgatorial experience of mutual suffering. One

lesser-known but excellent Catholic-themed work from Ford is 3 Godfathers, in which three bandits

become the unlikely godparents and self-sacrificial saviors of an infant in the

desert, in a way that parallels the story of the three Magi.

As a director, Alfred Hitchcock returned again and again to themes

of innocence and guilt; to tales of innocent men who find themselves entangled

in a world of espionage, or mistaken identity, or crime, who must reorder the

situation according to a higher standard of justice. Hitchcock also had a knack

for adding Catholic depth to his best thrillers by grounding the hero’s

adventures in a moral dilemma. Rear

Window, for instance, raises the question of whether voyeurism is ethical if

it allows one to prevent or uncover crime, when a man with too much time on his

hands begins spying on his neighbors and suspects one of murder. In Rope, the protagonist grapples with the ugliness

of intellectual pride—and how it spawns other grave sins. Hitchcock’s most

obvious return to his Catholic roots, however, was in I Confess, a chilling

examination of a (flawed) priest who keeps his vow to uphold the secret of the

confessional even when he is falsely accused of murder as a result.

As a director, Alfred Hitchcock returned again and again to themes

of innocence and guilt; to tales of innocent men who find themselves entangled

in a world of espionage, or mistaken identity, or crime, who must reorder the

situation according to a higher standard of justice. Hitchcock also had a knack

for adding Catholic depth to his best thrillers by grounding the hero’s

adventures in a moral dilemma. Rear

Window, for instance, raises the question of whether voyeurism is ethical if

it allows one to prevent or uncover crime, when a man with too much time on his

hands begins spying on his neighbors and suspects one of murder. In Rope, the protagonist grapples with the ugliness

of intellectual pride—and how it spawns other grave sins. Hitchcock’s most

obvious return to his Catholic roots, however, was in I Confess, a chilling

examination of a (flawed) priest who keeps his vow to uphold the secret of the

confessional even when he is falsely accused of murder as a result.

To be a Catholic means that the Catholic view of reality shapes

all we do, including the art we produce. The confidence in the existence and

importance of invisible things like moral principles, the fundamental goodness

of life, and man’s need for grace and redemption—these things deep in the spiritual

heritage of cinematic masters like Ford, Capra, or Hitchcock, are unmistakably

reflected in their artwork. Even if they were—like most of us—not perfect

Catholics, the themes and focus of their films prove they are the fruit of a

fundamentally Catholic perspective. They saw with Catholic eyes.

Lauren! I was catching up on reading my friends blogs and I was drawn to read this post. Very informative! I really like the movie I Confess. That picture of Montgomery Clift is priceless and I may have to steal it from you! Lol!

ReplyDeleteEnjoyed this piece :-)

ReplyDelete